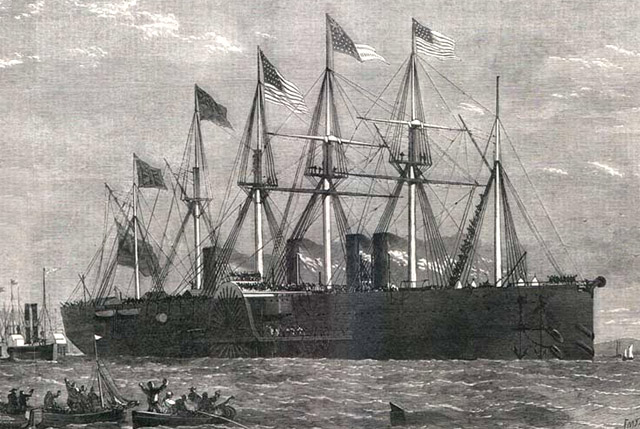

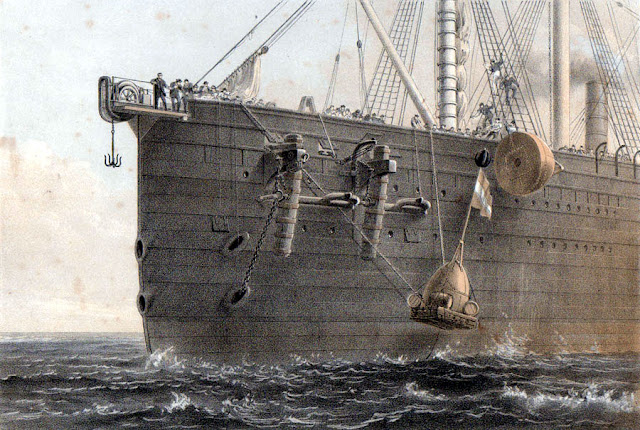

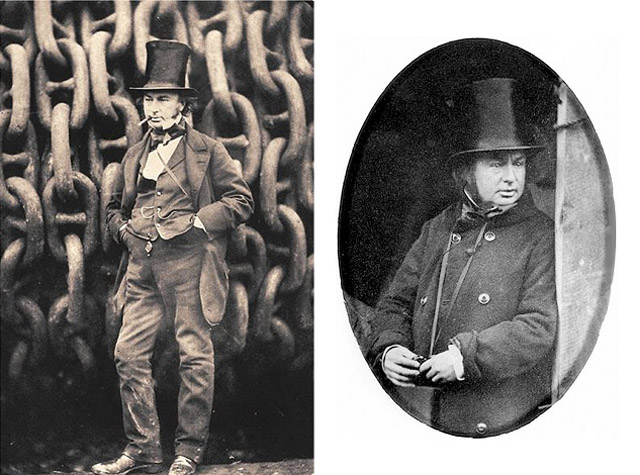

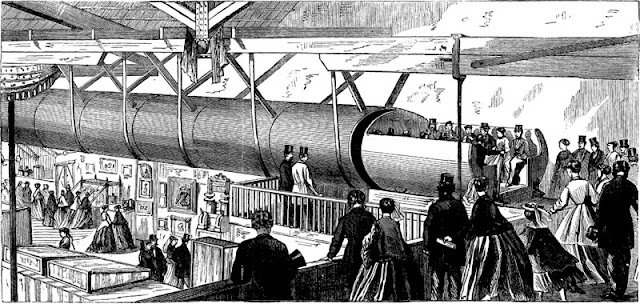

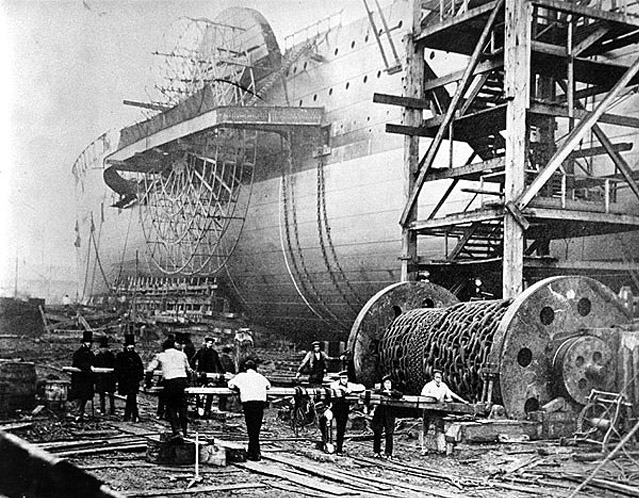

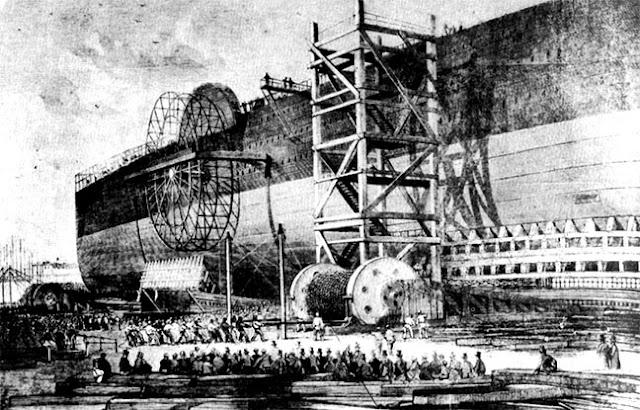

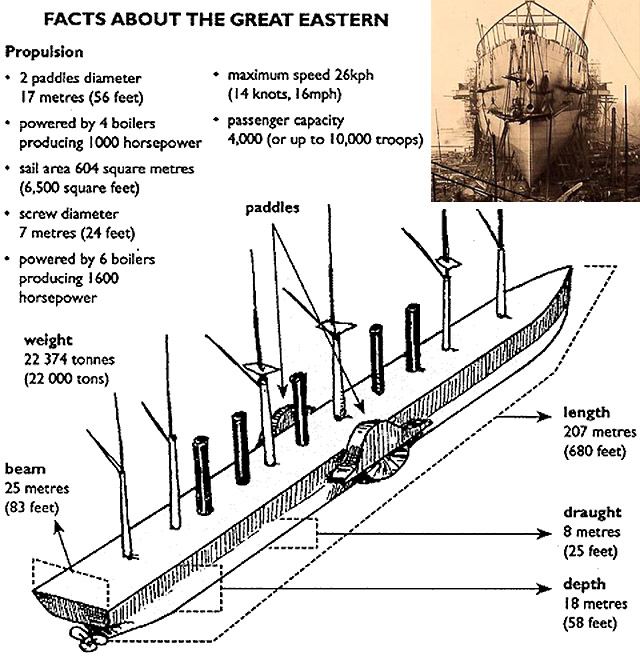

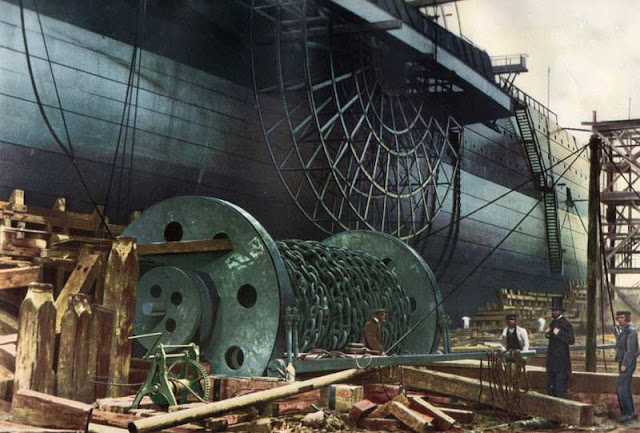

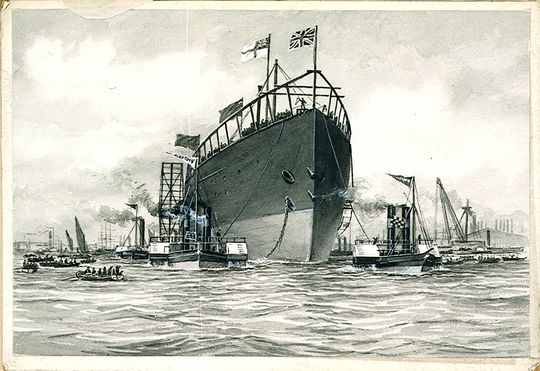

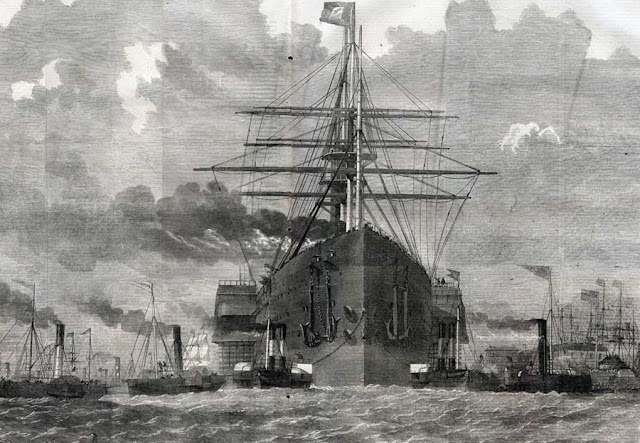

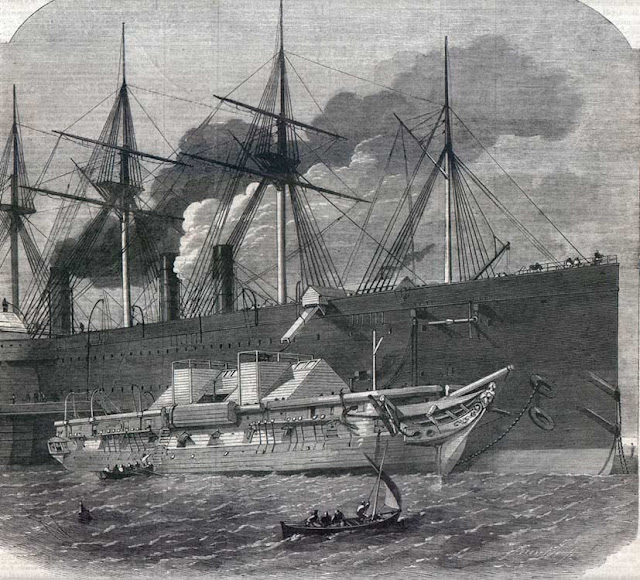

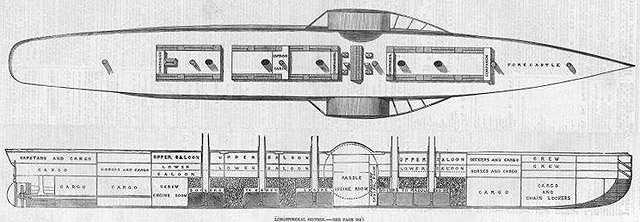

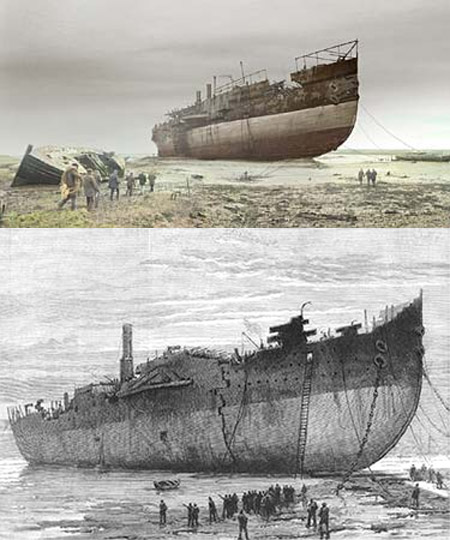

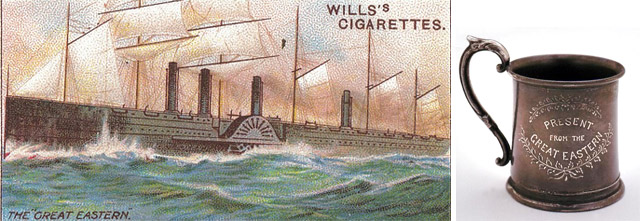

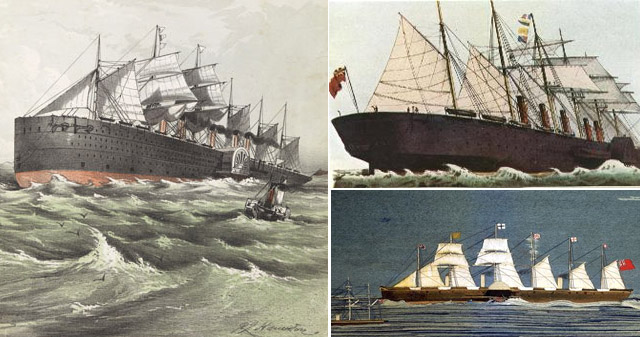

"QUANTUM SHOT" #457 "QUANTUM SHOT" #457link This article is co-written by author M. Christian (from "Meine kleine fabrik") and Avi Abrams. M. Christian loves to write about the odd, weird, and wonderful things hidden all around us. The More-Than-Great "Great Eastern" - one of the most spectacular ships ever built! Take a good long look at this ship. Built in 1858, it was capable of bringing 4,000 people around the world, without ever once needing to refuel... An Iron Monster, framed in a cloud of billowing white sails, or looming through the hellish black smoke - this was the ultimate Victorian luxury Trans-Atlantic liner, affectionately called the "great babe" by its eccentric designer:  Great Eastern leaving America with the 1866 Atlantic cable on board (art fragment)    (images credit: Robert Dudley, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London) We will see more of this ship, but first let's consider the extraordinary figure of its designer, and a fantastic era he lived in. An introduction to Victorian grandiosity: The Victorians - and so you don't have to look it up, means the British and U.S. during the reign of Queen Victoria, from about 1837 to 1901 -- did some truly great things. Theirs was an glowing-brass and crusty-iron era of chugging, whistling, hissing wonders. Nothing, they seemed to think, was impossible: the answer to every question, every engineering challenge, was just the matter of finding the right kind of steam engine for the job. One of their greats was the legendary Crystal Palace:  Although the Palace wasn't powered by coal, it was certainly fueled by Victorian mechanical audacity. Originally set up in Hyde Park in 1851 for the Great Exhibition, though later expanded and moved, the Palace was a transparent monster of a building, a huge greenhouse made up of 900,000 square feet of glass supported by an iron framework:  (image credit: buildinghistory) 900,000 may not sound like much but keep this in mind: the Palace was home to more than 14,000 exhibits. The Palace was something no one had seen before, a precisely engineered celebration of British innovation. The future had arrived in Hyde Park, and it was a tomorrow of crystal and steel. Another Victorian great was ... well, it might not have been as spectacular as the Crystal Palace but it was still something that made the people of London sit up and take notice. Or perhaps sit down and take notice. We take sewers and such for granted now but back then it was a true technological miracle, especially when executed on giant Victorian scale. Before Joseph Bazalgette began his work, London was a filthy nightmare. Decades, and more than 1,000 miles of pipe and connections later, the great city had become a marvel of cleanliness: a tomorrow of (mostly) clean streets and sweet smells. Enter: Isambard Kingdom Brunel But perhaps the greatest of the great Victorian engineers was a rather small man with very big dreams. At just about five feet, Isambard Kingdom Brunel wasn't a striking figure but what he lacked in height he made up with towering ability. Sure, some of his ideas didn't ... well, work out that well, but no one denies his mechanical genius. Even in failure some of his works were more advanced than the successes of his contemporary engineering rivals. Some say, "he was the most intense man in the business, the greatest artist ever to work in iron. He smoked 40 cigars per day and slept 4 hours per day."  (image credit: Robert Howlett) First brush with death: thrown into the awful maelstrom One of his early projects, and the one that almost killed him, was a tunnel. Okay, there were already a lot of tunnels -- and the Victorians took to tunneling like the Romans took to aqueducts -- but this one was different. It was a tunnel under the Thames, London's legendary river.  (Thames Tunnel; a diving bell used in its construction) But even Brunel's engineering skills weren't a match for the simple weight of all that water. Even with the city's sewer advances the river was more like a toilet than a body of water, so when it leaked -- which the tunnel did a lot -- what came dripping down from the ceiling wasn't ... shall we say, in a dry British way, "pleasant."  (image credit: International Urban Glow) It all went very wrong in 1828. When part of the tunnel collapsed, a monstrous wave of filthy water roared down on Brunel, knocking him unconscious and propelling him toward a very nasty death. Luckily an assistant managed to reach out and grab the master engineer before his diminutive boss got sucked into that awful maelstrom. Brunel never completely recovered from his injuries, but instead of retiring to dreams of steam-driven wonders, Brunel went on to build everything from immense bridges to the advanced (but unsuccessful) "atmospheric caper" pneumatic railway (more info). Here is a similar creation - "The Pneumatic Passenger Railway", 1867 by Alfred Ely Beach :  An impressive suspension bridge that he designed for Clifton in Bristol:  He then tackled the biggest and grandest of his big, grand projects -- what many folks see as one of the most spectacular ships ever built. An iron-riveted mountain, a black-smoke metal volcano Like with those 900,000 square feet of glass or 1,000 miles of sewer pipe, just prattling off the numbers doesn't do Brunel's Great Eastern justice. Its true scale can be better appreciated from these construction photographs:   (image credit: victorianweb.org) Although many innovations were used in the ship's construction, it was still mostly built by hand, with thousands of workers pounding the iron out of its hull from the first laying of its keel to its ultimate launch in 1858.  (image credit: scripophily)  (image credit: marine-marchande) There is a very intricate 3D model of the "Great Eastern" construction, on display at National Maritime Museum -  (John Scott Russell's shipyard, 'Great Eastern' under construction, courtesy National Maritime Museum) When you look at pictures of the Eastern, at first it doesn't look like much; just a typical ship of that era with, perhaps, some odd details. For instance, the Eastern had side wheels, propellers, and even sails on six huge masts. But look closer at some of those old illustrations and daguerreotypes. See those tiny little boats next to the Eastern? Well, they weren't that tiny, and the Eastern was anything but typical:  Seeing The Great Eastern chugging through a harbor or across the ocean must have been like watching an iron-riveted mountain, or a black metal volcano -- when it's five funnels were pouring black smoke into the sky from its 10 boilers fed by 100 furnaces -- crushing across the sea.  (image credit: porthcurno) Okay, she was big -- you've got that. But I still don't think you really get how big Brunel's ship actually was. For instance, although the crew of the ship was around four hundred, but she was built to carry 4,000 passengers -- the population of a pretty good sized town. And this was in 1858. She also carried enough coal to take those 4,000 passengers a good, long distance. Around the world, in fact, without ever once needing to refuel. The Cable Ship But the Great Eastern's most famous job wasn't shuttling passengers across the Atlantic. The Victorians had a great fondness for boilers, condensers, pistons, furnaces, and the stacks of steam power, but they'd also begun to harness the power of lightning -- or at least enough of it to send dots and dashes across a wire. The telegraph was a revolution but it was mostly limited to the continents. If you wanted to write Aunt Joan in New York you still had to put pen to paper and trust the post. Until the Great Eastern laid the transatlantic cable.  (image credit: Robert Dudley, Atlantic Cable) Time for numbers again: 2,600 miles of cable is what the Eastern carefully laid out across the Atlantic and later, across the Indian Ocean. Twenty-six-hundred miles when one kink, one break, would mean having to start all over again. That's a tremendous endeavor to try even today, let alone when men wore stovepipe hats and horses were still the preferred method of traveling on land. Two great ships: the "Great Eastern" & the "Titanic". Both suffered a damage to their hull. One sunk, one didn't. SS "Great Eastern" was also incredibly modern, boasting double hull construction (far ahead of its common use) and even gas lighting. It is this DOUBLE HULL that kept her afloat in the same circumstances that sent the "Titanic" to its doom. According to this source, here is a comparison with the Titanic: - Both the Titanic and the Great Eastern were the largest ships of their time. - Each suffered nearly the same accident, with utterly different results. - The Great Eastern featured fifty water-tight compartments, and a maze of bulkheads. - The Titanic's hull had only a single wall on each side!.. And even though the hull was divided in fifteen sections, which were designed to be sealed on a moments notice, "the bulkheads between those sections were riddled with access doors to improve luxury service"  The Great Eastern compartment plan The Great Eastern suffered a huge 83-foot-long, 9-foot-wide gash, after the encounter with an uncharted rock in Long Island Sound in 1862. But the inner hull held, and the ship remained afloat. The Titanic did not suffer anything like the huge continuous gash in the side of the Great Eastern: According to these recent acoustic imaging results, Titanic's hull "had not been gashed at all, but had been punctured in six of its forward compartments with a series of thin slits amounting to no more that 12 square feet."  No double sidewall ensured the fate of famous luxury liner, sending it to the depths in less than three hours. Huge ship takes 2 years to dismantle Alas, the end of the Eastern came with more of a whimper than bang. After suffering far too many accidents, and far too many money troubles, the Eastern passed from one hand to another until eventually the largest ship in the Victorian world came to a humiliating end, first as a floating billboard in Liverpool and then finally broken up and sold as scrap.  (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)  (image credit: National Maritime Museum) - It took two ful years just to dismantle this ship (gives you an idea how big it was). - A mysterious dead body was found inside that special double hull (one can only imagine the desperate story of that stowaway...) Some memorabilia: a depiction of "Great Eastern" on a cigarette card (see a great set of them) and a vintage coffee cup:  (images credit: mando_gal and National Maritime Museum) At least Brunel didn't see the sad and pathetic end to his magnificent Great Eastern, though he didn't live to see its majesty either. Brunel died only four days after the great ship's first sea trial. Brunel, fortunately, has remained an engineering legend, though his mighty Great Eastern has become nothing but a curiosity, a footnote in the history of Victorian grandiosity and innovation. But you could say "The Great Eastern" left at least a pretty BIG footnote in the annals of history.  (Other sources used: 1, 2, 3) READ THE WHOLE SERIES HERE -> Permanent Link...  ...+StumbleUpon ...+StumbleUpon  ...+Facebook ...+Facebook Category: Boats / Ships, Vintage Dark Roasted Blend's Photography Gear Picks: |

The Last Victorian Leviathan Steam Ship

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Check out this stream

Blog Archive

-

▼

2008

(968)

-

▼

August

(187)

- Link Latte 76

- Dancing Coloring Pages

- Funny Cowboy Coloring Pages

- Playing Piano Coloring Pages

- Book Worm Coloring Pages

- Cute Baby Coloring Pages

- Alien Coloring Pages

- Nice Family Coloring Pages

- Ornamental Coloring Pages

- Little Mermaid Coloring Pages

- Coloring Book

- Some of the World's Strangest Fences

- Aeroplane Coloring Pages

- Flowers Life Coloring Pages

- Dragon Coloring Pages

- Little Doggie Playing..

- Custard Kitty Coloring Pages

- Cool Cat Player Coloring Pages

- White dongle

- Bratz Doll Coloring Pages

- Transparent Underground

- Harmony Coloring Pages

- Coloring the World!

- Tinkerbell and Flower!

- Hibiscus Flower Coloring Pages

- Butterfly and Flower Coloring Pages

- Flower Coloring Pages

- 3 Flowers Bloom

- Bouquet of Roses

- Little Flower Coloring Pages

- Monowheels: The Weirdest Transport Known to Man

- Accidents Big and Small

- Robots: Art & Technology

- Fairy Coloring Pages; Resting

- Flower Fairy Coloring Pages

- In the Jungle

- Teenage fairy coloring pages

- Moon Fairy Coloring pages

- Silly Fairy Coloring Pages

- Fairy Coloring Pages

- Space Opera, Mexican Style

- Tinkerbell's Glimpse

- Tinkerbell Clapsing Hands

- A Big Gigle From Tinkerbell

- Preening Tinkerbell

- Resting Tinkerbell

- Angry Tinkerbell

- Jealous Tinkebell

- Hiding Tinkerbell

- Tinkerbell in the Ship

- Gigantic City-Structures of Paolo Soleri

- Link Latte 75

- Never Give Up! - Funny Pics, Part 9

- House Coloring Pages...

- Tiny Fairy Coloring Pages

- Smiling Fairy Coloring Pages

- Funny Fat Fairy

- Printable Fairy Coloring Pages

- Funny Tiger Coloring Pages

- Horse Coloring Pages

- Lamb Coloring Pages

- Family Guy Coloring Pages

- Grilling Coloring Pages

- Master Yoda Coloring Pages

- Drunk Animals in Africa

- Psychedelic Furniture, Part 2

- Funny Koala Coloring Pages

- Funny Bunny Coloring Pages

- Bird in spring season

- Cute Tiger Coloring Pages

- Cute Coloring Pages

- Lighthouses vs. Huge Waves

- Spider Webs Glamour & Architecture

- Butterfly Playing Ground

- Fat Butterfly Coloring Pages

- Butterflies in the sky

- Large Wing Butterfly Coloring Pages

- Butterfly Coloring Pages 2

- Butterfly Coloring Pages

- Link Latte 74

- Garfield Coloring Pages: Beach..

- Garfield Coloring Pages: Sleeping Time...

- Garfield Coloring Pages: Fall in Love

- Garfield Coloring Pages: Lunch!

- Garfield Coloring Pages

- Aladin Coloring Pages

- Cartoon Turtle Coloring Pages

- Learn to draw Dragon

- Tinkerbell Color Flower

- Care Bear Coloring Pages

- Sylvester tricky fire!

- Crazy Wiring, Part 5

- Love. Song. Italy...

- Sailormoon and Friends

- Naruto Coloring Pages

- Sailormoon Coloring Pages

- Cockatoo Coloring Pages

- New Bird Born Coloring Pages

- Yeehaa Coloring Pages

- Dora Coloring Pages: Swiper! No Swiping!

-

▼

August

(187)

0 comments:

Post a Comment